ANTI-CANDIDA ALBICANS EFFECT OF IMPATIENS WALLERIANA AERIAL EXTRACT

HTML Full TextANTI-CANDIDA ALBICANS EFFECT OF IMPATIENS WALLERIANA AERIAL EXTRACT

Gauri Kulkarni *, Shreya R. Naik, Sadhana Chougale, Nisarga Pol and Shilpa Sunkad

NITM-ICMR, Belgaum, Karnataka, India.

ABSTRACT: The genus Impatiens encompasses a diverse array of species valuable as sourcs of natural medicine some of which remain unexplored and insufficiently characterized. Impatiuens is a reservoir of metabolites such as phenolics, phytosterols, triterpenoids, and peptides which exhibit spectrum of activities including antimicrobial, cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-anaphylactic. Impatiens walleriana belonging to the family balsaminaceae is known for its aesthetic appeal and as folk medicine. Drug resistant strains of Candida and Aspergillus have made fungal infection treatment difficult and plants are serving as good alternatives. Impatiens walleriana is anti-microbial and traditionally applied to skin in folk medicine but has not been specifically screened for its anti-Candida albicans effectiveness hence, the present in-vitro study. The hydroalcoholic extract of the aeria parts of Impatiens walleriana has shown anti-Candida albicans effect with MIC 3.3mg/ml and ZOI ranging from 9mm to 20mm with maximum effectiveness at 100mg concentration in the triplicate readings taken for the selected doses 50mg, 100mg and 200mg.

Keywords: Anti-fungal, Candida albicans, Impatiens walleriana, and in-vitro studies

INTRODUCTION: The development of invasive fungal infections is a significant health problem particularly in immunocompromised and hospitalized patients. These fungal infections are associated with a high mortality and morbidity rate 2. The most commonly identified Candida species in hospitals is Candida albicans. The rise in antifungal resistance around the world is one of the greatest emerging health problems, making it difficult to select effective antifungal treatments 3, 4. Many strains of Candida albicans are resistant to current antifungal drugs, including azoles and echinocandins 5.

A significant factor in the development of Candida albicans resistance is extended exposure to antifungal drugs, particularly the excessive use of azoles and echinocandins as prophylactics, or the empiric treatment of patients at risk of developing invasive candidiasis. Candida species are normally harmless microorganisms that inhabit the oral, gastrointestinal, urinary and vaginal mucosal surfaces of humans 6, but they can behave as opportunistic pathogens with the ability to cause both superficial and invasive systemic fungal infections.

The Candida genus is, in fact, the most frequently isolated cause of hospital-associated fungal infections, broadly referred to as candidiasis. Although over 150 species are included within this highly diverse genus, only a small number are recognized as significant agents of human disease. One of the key virulence traits of Candida is its capacity to survive in multiple environments and to form surface-adhered microbial structures called biofilms 7. Fungal diseases also known as mycoses are infection caused by fungi. They can affect various parts of the body ranging from skin and nails to internal organs. Candida species are commensal micro-organisms in human oral mucosa, digestive and vaginal tract and spread of this opportunistic fungus happens when host immune system is broken down. These infections can be superficial such as thrush, vaginitis, skin infection or invade the blood stream and spread to any site of human host which cause many clinical complications such as brain abscess, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis etc 9.

Medicinal plants have traditionally been used for managing fungal infections, offering a rich source of bioactive compounds for new drug development. Plant-based therapies are gaining popularity as safer, multi-target alternatives to conventional treatments, particularly in fungal infection, which accounts for nearly one-fifth of dermatology visits. Medicinal plants remain essential to global healthcare, particularly in developing regions where traditional medicine is widely practiced. Historically, over 80% of medicines were plant derived, and herbal knowledge has significantly contributed to pharmaceutical development. Their continued use is attributed to perceived safety, effectiveness, affordability, and minimal side effects, yet much of this traditional knowledge often passed down orally is at risk of being lost without documentation 9, 10.

Medicinal plants such as Impatiens walleriana are rich in phytochemicals and hold promise as natural antifungal agents 6-8. Among such plants, the genus Impatiens is known for its antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and anti allergic activities. Impatiens walleriana, an ornamental species from the Balsaminaceae family used in folk medicine, displays antioxidant, antibacterial and antifungal properties 6, 5. Since, this plant is traditionally applied to the skin, easily available, rich in minerals and considered safe. Impatiens is extensively distributed across the globe and is easily cultivated in various settings such as home, gardens, green houses and public parks. This research focuses on assessing the aerial extracts of Impatiens walleriana for the potential antifungal properties 10.

Impatiens walleriana has not been screened for anti-fungal activity. In the present study extract of this plant has been evaluated for antifungal activity 10, 11.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: The fresh plants were first washed under running tap water and root portions were removed followed by drying in shade at room temperature. Dried plant material was ground to coarse powder and stored in an air tight bottle. Extraction was done using 75% hydro alcoholic solvent by maceration for 72 hours. An orbital shaker was used to mix plant material and solvent uniformly during extraction, enhancing the release of active compounds. Solvent was removed by evaporator using water bath and residue was scraped by using spatula and collected followed by weighing and calculation of % yield.

% Yield = 𝑊1/ 𝑊2 × 100

Where, W1 = weight of the extract after extraction. W2 = weight of plant powder.

MIC Test Procedure: 9 dilutions of each drug have to be done with Thioglycolate broth for MIC.

- In the initial tube 200µl Compound of desired percentage concentration is added into 200µl of TGB (Tube 1).

- For dilution 200µl of TGB are added in to the next 9 tubes separately (Tube 2 to Tube 10).

- Then from second tube 200µl was transferred to the next tube contacting 200µl of TGB. This was considered as 10-1 dilution.

- From 10-2 dilution tube 200µl was transferred to the tube 3 (T3) to make 10-2 dilution.

- The serial dilution was reported up to 10-9 dilution for each drug. As shown in 1.

- From the maintained stock culture of required organisms 5µl was taken and added into 2ml of TGB.

- In each serially diluted tube 200µl of above culture suspension was added.

- The tubes were incubated for 48-72 hours in anaerobic jar at 37°C and observed for turbidity.

- For MIC of Compound antibiotic tetracycline 10mg mixed with 1ml distilled water: 1% Compound prepared and performed the MIC as per the above instructions.

Disc Diffusion Test Procedure:

- Media used: Brain Heart Infusion agar

- Temperature: Bring agar plates to room temperature before use

- Inoculum Preparation:

- Using a loop or swab, transfer the colonies to the plates.

- Visually adjust turbidity with broth to equal that of a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard that has been vortexed. Alternatively, standardize the suspension with a photometric device.

- Inoculation of Agar Plate:

- Within 15 min of adjusting the inoculum to a McFarland 0.5 turbidity standard, dip a sterile cotton swab into the inoculum and rotate it against the wall of the tube above the liquid to remove excess inoculum.

- Swab entire surface of agar plate three times, rotating plates approximately 600 between streaking to ensure even distribution. Avoid hitting sides of petriplate and creating aerosols.

- Allow inoculated plate to stand for at least 3 minutes but no longer than 15 minutes before making wells.

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare the stock solution weighing 50mg, 100mg and 200mg of compound and dissolve it in 1ml DMSO

- Addition of Compound into Plate:

- Take hollow tube of 5mm diameter, heat it. Press it on above inoculated agar plate and remove it immediately by making a well in the plate. Likewise, make 5 well on each plate.

With the help of micropipette add 50µl of each concentration prepared in each well. This will be done for one compound when they want to know the quantity grading. If they want to compare between different compounds then in one plate different compounds will be put with fixed quantity i,e. 50µl. As shown in Fig. 2A, B, C and D.

- Incubation:

- Incubate plates within 15 min of compound application.

- Invert plates and stack them no more than five high.

- Incubate for 18-24 hours at 37 °C in incubator.

- Reading plates:

- Read plates only if the lawn of growth is confluent or nearly confluent.

- Measure diameter of inhibition zone to nearest whole millimeter by holding the measuring device.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION:

Results: Impatiens walleriana extract has resinous consistency and brown appearance and earthy & classy odour. The yield of extract in the present study was found to be 13.75%.

- Percentage yield of Impatiens walleriana extract

- Weight of dried Impatiens walleriana sample: 80gm

- Weight of Impatiens walleriana extract: 11gm

- Yield of extract was found to be: 13.75 % w/w

FIG. 1: RESULTS OF MIC

TABLE 1: MIC RESULTS

| Tube | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Constituents | 200µl1%Comp+200µl TGB | 200µl1%Comp+200µlTGB+200µlOrg | 200µl0.33%Comp+200µl TGB+200µlOrg | 200µl0.11%Comp+200µlTGB+ 200µlOrg | 200µl0.04%Comp+200µlTGB+200µlOrg | 200µl0.013%Comp+200µl TGB+200µlOrg | 200µl0.0433%Comp+200µlTGB+200µlOrg | 200µl0.01433%Comp+

200µlTGB+200µlOrg |

200µl 0.004811% Comp+200µlTGB+200µlOrg | 200µl0.1603X104%

Comp+200µlTGB+200µlOrg |

PC200µlTGB+

200µlOrg+200µlITR |

NC200µlTGB+ 200µlComp |

| Compound concentration (in %) |

0.5 |

0.33 |

0.11 |

0.04 |

0.013 |

0.0433 |

0.014433 |

0.004811 |

0.1603X104 |

0.055X102 |

50 |

50 |

| Compound Concentration (inmg/ml) |

5 |

3.3 |

1.1 |

0.4 |

0.13 |

0.433 |

0.14433 |

0.04811 |

1.603X104 |

0.551X102 |

5 |

5 |

| Dilution

Factor |

Neat | 10-1 | 10-2 | 10-3 | 10-4 | 10-5 | 10-6 | 10-7 | 10-8 | 10-9 | - | - |

| Candida albicans | S | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | √ | √ |

Note: S=Sensitivity, R=Resistant

Results of Disc Diffusion Method:

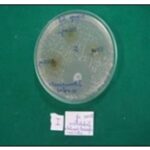

FIG. 2A: ZOI RESULTS (I SET)

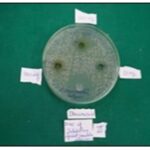

FIG. 2B: ZOI RESULTS (II SET)

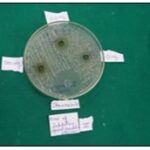

FIG. 2C: ZOI RESULTS (III SET)

TABLE 2: ZONE OF INHIBITION AGAINST CANDIDA ALBICANS

| Compound concentration (in mg/ml) | 50 | 100 | 200 | Control (Tetracycline) |

| Candida albicans | ||||

| I Set | 15mm | 20mm | 16mm | 25mm |

| II Set | R | 18mm | 09mm | 24mm |

| III Set | R | 17mm | 17mm | 26mm |

| Mean+SD | 5+8.66 | 18.33+1.52 | 14+4.35 | 25+1.0 |

Statistical Analysis: All experiments were performed with 3 replicates of each treatment (I Set, II Set, III Set).

Statistical analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2007. Data are expressed as means ±SD.

DISCUSSION: Medicinal plants contain bioactive compounds with strong therapeutic benefits. They are studied as alternatives to antibiotics due to safety and efficacy, and can supplement current antifungal therapy.

The present study evaluated the antifungal activity of Impatiens walleriana extract against Candida albicans using the agar well diffusion method. Interestingly, the results revealed that lower concentrations of the extract produced larger zones of inhibition compared to higher concentrations, indicating a non–dose-dependent response. In contrast to a typical dose- dependent effect, where increased concentration correlates with enhanced antimicrobial activity, the inhibitory effect of this extract does not follow a strictly proportional relationship 12, 13.

Several factors may account for this observation. Minor variations in experimental conditions, such as agar thickness, well dimensions, or inoculum density, could influence diffusion and activity. Additionally, at higher concentrations, certain bioactive compounds may exhibit reduced solubility or instability, thereby diminishing their antifungal efficacy. Interactions among multiple constituents within the extract may also contribute, where some compounds potentially antagonize the activity of others at elevated concentrations 14, 15.

These findings underscore the complexity inherent in plant-based extracts, which often comprise a mixture of bioactive molecules with variable effects. While Impatiens walleriana demonstrates significant antifungal potential, the lack of a strictly dose- dependent response highlights the necessity for careful optimization of extract concentration. Further studies focusing on the isolation of active compounds and mechanistic investigations are recommended to elucidate the factors influencing the observed activity and to determine the most effective concentration for potential therapeutic applications 15.

The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of the extract at which the bacteria does not demonstrate visible growth. Results of zone of inhibition are large in lower concentration than the higher concentration. As depicted in Table 2. The MIC results 3.3mg/ml for this experiment. Here once the dilution goes on increasing the concentration decreases. First it was 5mg/ml then it comes to 3.3mg/ml. As depicted n Table 1. The MIC result for our compound was found to be 3.3mg/ml. Usually, when the concentration of a compound is increased, the Zone of Inhibition (ZOI) should also increase. But in our case, the opposite has happened it has reduced. For 50 mg, the ZOI was resistant. For 100 mg, it showed 15 mm in the first set. After 100 mg, it showed proper results, but after 200 mg, the ZOI should have increased compared to the previous readings. However, it was reduced instead. This variation may be due to multiple factors

The zone of Inhibition is large in lower concentration than the higher concentration. Paradoxial effect (eagle effect): the eagle effect or paradoxial growth effect refer to the reduced efficacy of an antimicrobial agent at higher concentrations. Usually reported in echinocandians (Eg: capsofungin) and some azoles documents particularly in Candia Spp and Aspergillus Spp 16.

Precipitation at higher concentration/poor diffusion at higher concentrations, especially above solubility limit, compounds may precipitate, reducing diffusion in agar. This results in smaller or absent inhibition zones despite the high actual dose 15, 16. Toxicity to agar or organism environment at very high concentrations, some compounds alter pH, osmolarity, or denature proteins in agar leading to poor organism growth or misinterpreted resistance 15, 16. Certain antimicrobials (such as peptides or lipids) may aggregate or undergo concentration-dependent inactivation, reducing their biological activity 16, 17. At higher concentrations or over time, some compounds may degrade into by-products that either antagonize antimicrobial activity or interfere with microbial growth 17.

CONCULSION: The present study revealed that Impatiens walleriana extract possesses significant antifungal activity against Candida albicans. Interestingly, the inhibitory effect did not follow a strictly dose-dependent pattern, as lower concentrations produced larger zones of inhibition than higher concentrations. Minor variations in experimental conditions, including agar thickness and inoculum density, may also influence the observed activity. These results highlight the inherent complexity of plant-based extracts, which often contain a mixture of compounds with variable effects. The findings emphasize the need for careful optimization of extract concentration to achieve maximal antifungal efficacy. Further investigations focusing on the isolation and characterization of active constituents are warranted. Additionally, mechanistic studies could provide insight into the factors influencing the extract’s activity. Overall, Impatiens walleriana demonstrates promising antifungal potential for future therapeutic applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Authors thank Dr. Harsha Hegde of NITM-ICMR, Belgaum for plant authentication and Ms. Shilpa SS of MM Central Research Laboratories, Belgaum for MIC. Authors also acknowledge Ms. Vaishnavi Mali and Ms. Gayatri Jadhav for assisting with laboratory work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Nil

REFRENCES:

- Anandani G, Bhise M and Agarwal A: Invasive fungal infections and the management in immunocompromised conditions. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2025; 14(7): 2643-52.

- Pfaller M, Diekema D, Turnidge J, Castanheira M and Jones R: Twenty Years of the Sentry Antifungal Surveillance Program Results for Candida Species from 1997–2016., Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2019; 6(1): 79-94.

- Jawhara S: How Gut Bacterial Dysbiosis can Promote Candida albicans Overgrowth during Colonic Inflammation, Microorganisms 2022; 10: 1014.

- Jawhara S: How Fungal Glycans Modulate Platelet Activation via Toll- Like Receptors Contributing to the Escape of Candida albicans from the Immune Response, Antibiotics 2020; 9: 385.

- Atriwal T, Azeem K, Husain F, Hussain A, Khan M, Alajmi M and Abid M: Mechanistic understanding of Candida albicans biofilm formation and approaches for its inhibition. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021; 12: 638609.

- Soll D: Candida commensalism and virulence: the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Acta Tropica 2002: 81: 101–110.

- Calderone RA: Introduction and historical perspectives. In: Candida and Candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington DC, USA, Calderone RA (Ed.) 2002.

- Chandra J, Kuhn M, Mukherjee P, Hoyer L, McCormick T and Ghannoum M: Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: development, architecture, and drug resistance. Journal of Bacteriology 2001; 15: 183: 5385-94.

- Talapko J, Juzbašić M, Matijević T, Pustijanac E, Bekić S, Kotris I and Škrlec I: Candida albicans the virulence factors and clinical manifestations of infection. Journal of Fungi 2021; 22(7): 79.

- Delgado-Rodríguez J, Weng-Huang L and Chang S: Ethnobotany, pharmacology and major bioactive metabolites from Impatiens genus plants and their related applications. Pharmacognosy Rev 2023; 17(34): 338–51.

- Lakschevitz F, Olman H, Loría-Gutiérrez A and Weng-Huang N: In-vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of ethanolic extracts from Impatiens species. Journal of Applied Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants 2022; 29: 100375.

- Douglas L: Candida biofilms and their role in infection, Trendsin Microbiology 2003; 11: 30– 36.

- Ganguly S and Mitchell A: Mucosal biofilms of Candida albicans, Current Opinion in Micro 2011; 14(4): 380–385.

- Shields R, Nguyen M and Press G: The eagle effect in Candida glabrata: paradoxical antifungal activity of echinocandins, Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2011; 55(11): 5122-5125.

- Stevens D, Espiritu M and Parmar R: Paradoxical effect of capsofungin: reduced activity against Candida albicans at high drug concentrations. Antimicrobial agents and Chemotherapy 2004; 48(9): 3407-3411.

- Wayne PA: CLSI performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI supplement M100, 31st edition 2021.

- Balouitei M, Sadiki M and Ibnsouda S: Method for in-vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2016; 6(2): 71-79.

How to cite this article:

Kulkarni G, Naik SR, Chougale S, Pol N and Sunkad S: Anti-candida albicans effect of Impatiens walleriana aerial extract. Int J Pharmacognosy 2026; 13(1): 40-45. doi link: http://dx.doi.org/10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.IJP.13(1).40-45.

This Journal licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Article Information

5

40-45

666 KB

21

English

IJP

Gauri Kulkarni *, Shreya R. Naik, Sadhana Chougale, Nisarga Pol and Shilpa Sunkad

NITM-ICMR, Belgaum, Karnataka, India.

gauri.rccp@gmail.com

23 December 2025

28 January 2026

29 January 2026

10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.IJP.13(1).40-45

31 January 2026